Nigeria

This document is part of a larger research project on African gold flows. For information on data sources, methodology or recommendations, please refer to SWISSAID’s 2024 report On the trail of African gold.

Country type

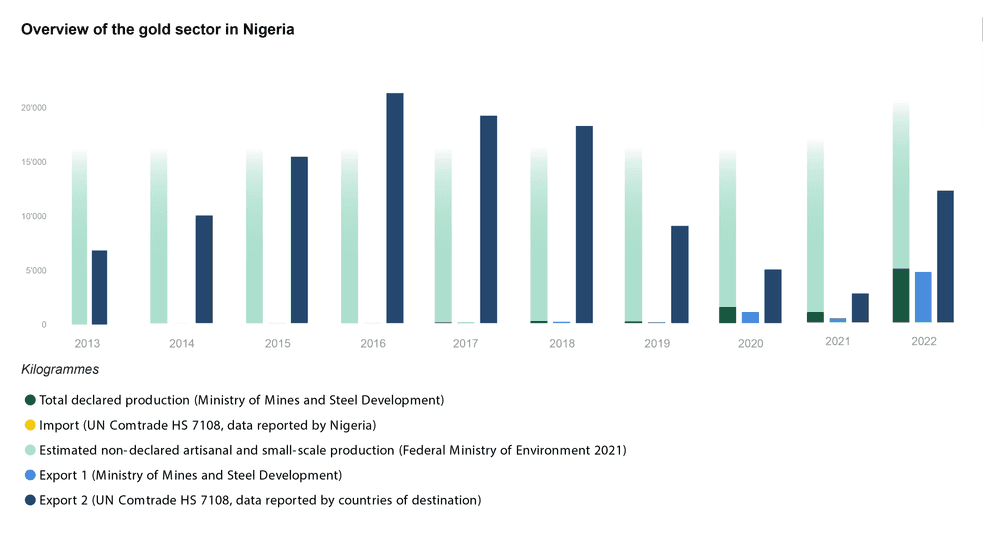

Main characteristics: sizeable gold production from artisanal and small-scale mining, most of which is smuggled out of the country and destined for the UAE; industrial production as well since 2022

Gold production

-

Artisanal and small-scale mining

- Declared: 1.96 tonnes in 2022

- Non-declared (estimate): between 14.3 and 15.6 tonnes per year in the early 2020s

-

Industrial or large-scale mining: 3.0 tonnes in 2022

Gold exports

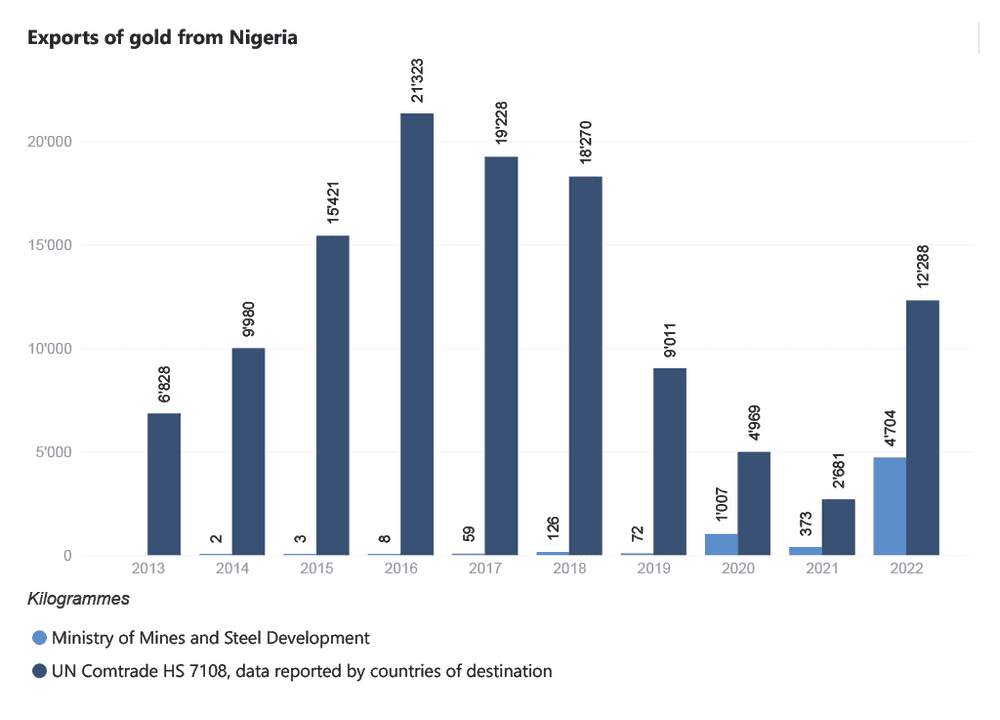

- Declared: 4.7 tonnes in 2022 (the bulk of which was industrial gold shipped to Switzerland)

- Non-declared (estimate): 97 tonnes between 2012 and 2018, so 13.86 tonnes per year on average

EITI member: yes

Reports to UN Comtrade: yes, but data on gold exports is missing or too low for every year between 2013 and at least 2020.

Summary

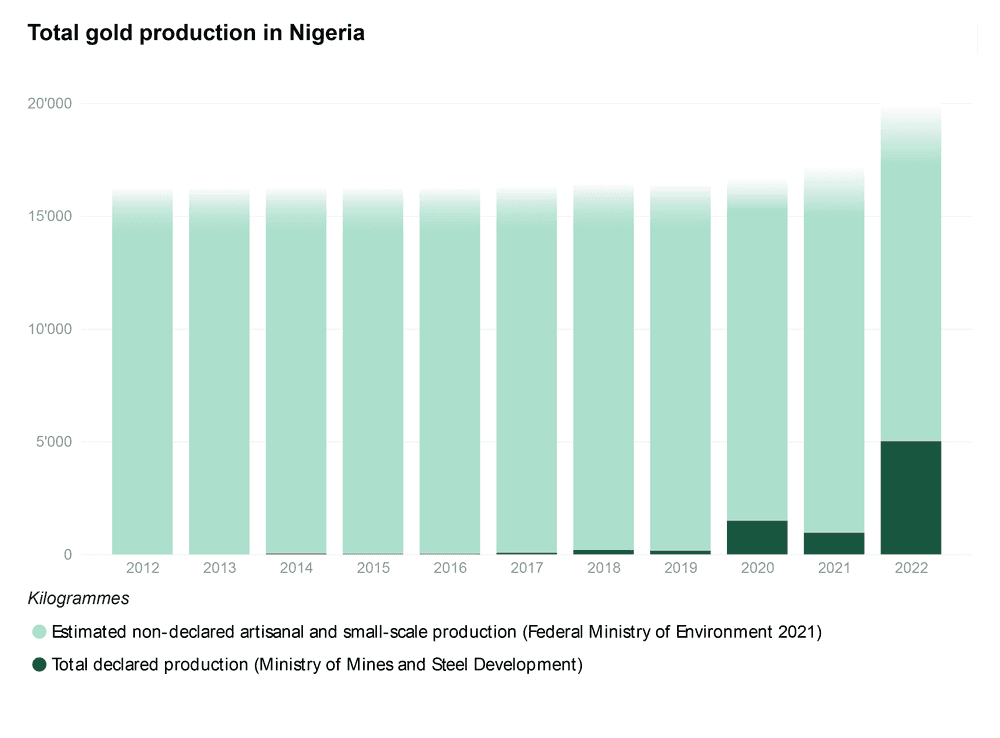

Nigeria is a medium-sized gold-producing country, according to African standards. Until recently, all of the country’s yellow metal originated from artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). The country’s first industrial gold mine only started commercial production in 2021. Nigerian ASM’s total gold output was estimated at 16.26 tonnes a year in the early 2020s. By contrast, official figures for this type of production in the 2010s rarely reached more than a few tens of kilogrammes. Figures for the 2020s are higher, which suggests that the Nigerian state could be recording larger amounts of ASM gold now than it was some years ago. However, they are nowhere near the estimate of more than 16 tons, which suggests that the bulk of the gold produced through ASM in Nigeria remains undeclared.

This gold is almost entirely smuggled out of the country and shipped to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), either directly or indirectly, i.e. through neighbouring countries. Niger, in particular, seems to have played an important role as a transit country for Nigerian gold in the second half of the 2010s. Undeclared gold exports over the decade 2013–2022 could amount to almost 114 tonnes in total. The Nigerian government acknowledged the scale of the phenomenon and its problematic nature on various occasions.

As for gold from Segolila, Nigeria’s only industrial mine, it is declared for export and sent to Switzerland for processing.

There are many unknowns regarding Nigeria’s gold sector. For one thing, Nigerian official figures on gold production and export are too low to be used as a basis for the analysis. That said, one can safely argue that Nigeria’s yearly gold output and exports were very significant between 2013 and 2022 and that they remained, until recently, almost entirely undeclared. This results not only from a comparison of official Nigerian figures with the most reliable estimates and the most comprehensive accounts of the gold business in Nigeria, but also from a comparison of these estimates with the imports of yellow metal from this country reported by the authorities of the other countries (most notably those of the UAE): in some years, these imports reach a similar level as the estimates, which suggests that the latter are realistic, and that the volumes are actually much larger than what is declared.

Gold production

In Nigeria, gold is mined by artisanal and small-scale methods as well as, in recent years, industrial or large-scale ones (see, e.g. Nairametrics 2022). SWISSAID looked for official figures on the production of each of these subsectors taken separately, but did not find any. It seems that the Nigerian authorities only communicate figures on total production of the precious metal.

It is widely acknowledged (see, e.g. This Day 2022, NEITI 2018: 57 and Environmental Law Institute 2014: 1) that only a very small portion of the gold that was extracted from Nigeria’s ground and riverbeds in the last decade was declared to or registered by state authorities. Indeed, official figures communicated to SWISSAID by the Nigerian Ministry of Mines and Steel Development (MMSD)1 for the period 2010–2019 are either non-existent or very low. Those for more recent years (2020 and 2021) are somewhat higher, but still one order of magnitude lower than estimates of ASM gold production (see below). As for the figure for 2022, it is much higher than the previous ones due mainly to the start of commercial production at Segilola, Nigeria’s first industrial gold mine (NEITI 2022: 31), in the first quarter of that year (Mining Weekly 2022). Segilola produced 309 kg (9,921 ounces) and 3,048 kg (98,006 ounces) of gold in 2021 and 2022, respectively (Thor Explorations 2023), and sent this material to Metalor, in Switzerland, for refining2.

The Nigerian government considers gold as a “strategic metal” and expects gold mining to play a key role in the economic development of the country. It has promoted gold mining through ASM in recent years, notably by granting a large number of licences (e.g. 352 licences in 2021, NEITI 2023: 32) and launching a national purchase programme (NEITI 2022: 30) in this field. However, it is unclear whether the Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Development Initiative (PAGMI), as the purchase programme is called (see: FMINO 2020), has allowed the government to buy more than a few tens of kilogrammes of gold so far. Indeed, it is likely that this programme has become dormant already.

To this day, artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Nigeria remains highly informal. An expert of the Nigerian gold sector who commented on SWISSAID’s analysis in September 2024 acknowledged that “the gold sector has been more in secrecy for a long time with low or no production data”, which he mainly attributed to trafficking. At the same time, the expert stressed that policy implementation by the current administration was leading to improvements in environmental compliance and production monitoring. He was confident that biometric data capture (see, e.g. Voice of Nigeria 2023 and Punch 2023), in particular, would improve available statistics on gold production in Nigeria3. SWISSAID is not able to assess the effectiveness of these recent efforts by the Nigerian authorities. Previous studies claimed that much is still needed to be done to enhance the formalisation of the Nigerian ASM sector (PWC 2023: 27), which is crucial considering the socio-economic and environmental impact on local communities that is at stake. Indeed, unregulated ASM has been proven to be associated with environmental degradation, poor health and numerous social vices in the country (Dibala et al. 2016).

According to the National action plan for the reduction and eventual elimination of mercury use in artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Nigeria, which was published by the Federal Ministry of Environment (FME) in 2021, Nigerian ASGM produces an estimated 16.26 tonnes of gold per year (FME 2021: 70). This figure is based on field studies conducted throughout the country in the late 2010s and early 2020s. As the FME explains: “From the analysis of the sites’ estimates in different States, estimates of gold and mercury productions per State were extrapolated to produce national estimates of 16,260.40 kg of gold produced by Nigeria’s ASGM sector” (FME 2021: 72).4 As the FME itself points out, this national estimate is vastly higher than the official figures released by the Nigerian state. For example, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS)’s statistics on the disaggregated mining and quarrying data, gold production in Nigeria only reached 64 kg in 2018 (NBS 2019).5 The FME concludes that “it is clear that government was missing out on important revenue accruable from the ASGM sector” (FME 2021: 72).

Gold imports

Official figures on gold imports into Nigeria indicate that the country received only small volumes of yellow metal in recent years. Total weights reported to UN Comtrade by the Nigerian authorities for 2012–2022 are zero or very small and those reported by their foreign counterparts are for the most part barely higher.6

SWISSAID is not aware of any gold having been smuggled into Nigeria during the same period. The country is known as the origin of sizeable illicit gold flows, as explained below, but not as a destination for such flows.

Gold exports

Although it is clear that a vibrant market for gold exists within Nigeria (see, e.g. Business Day 2022), figures on domestic consumption of the precious metal are lacking. Given the presence of both gold mines and gold refineries in the country, as well as the very low levels of gold imports, one can assume that a substantial part of domestic demand for the precious metal is met with gold that originates from the country’s own mine sites. But not much is known about the volumes involved. The lack of figures on Nigeria’s domestic gold market makes it difficult to take this aspect into account in analysing the country’s gold sector. Thus, what follows is based on the assumption that all gold produced in Nigeria is exported out of the country.

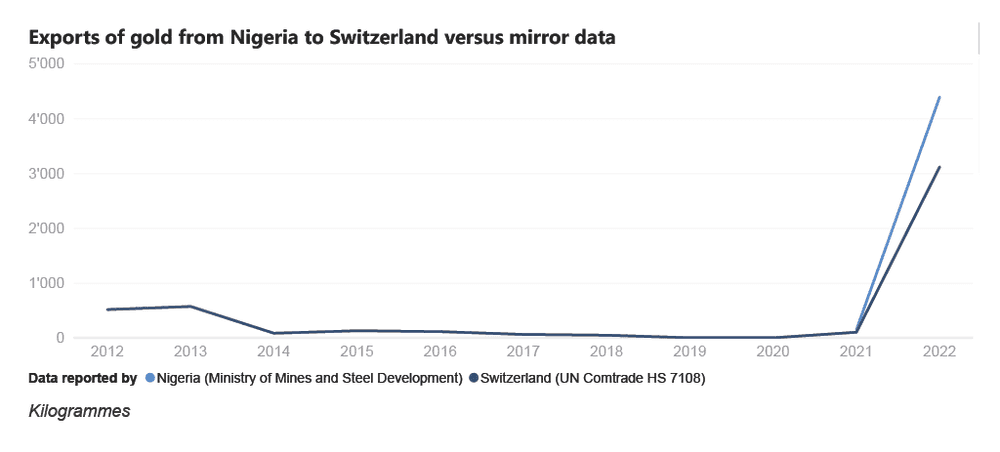

As the above graph shows, most of the gold that is declared upon entry in importing countries as originating from Nigeria is not declared for export in that country. Figures communicated to SWISSAID by the MMSD are very low for every year between 2010 and 2019.7 Like those on production, they are higher for subsequent years due, in part, to the start of industrial gold mining in the country. Nevertheless, even for those years, they remain far below the imports reported to UN Comtrade by the authorities of the other countries. The gap between the two datasets is wide for every year between 2010 and 2022 and amounts to 113.65 tonnes of gold in total over the last ten years (2013–2022).8 In all likelihood, this corresponds more or less to the amount of gold that was smuggled out of Nigeria during that period.

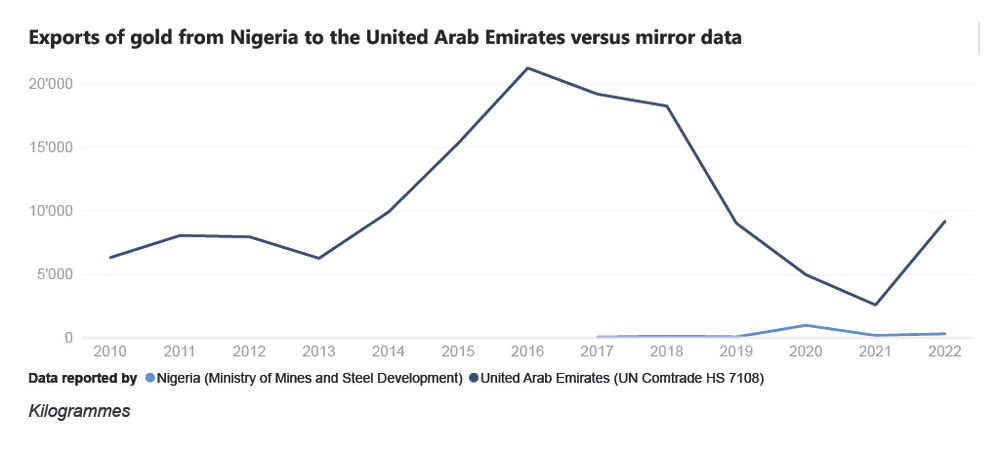

Gold that left Nigeria between 2010 and 2022 was headed almost exclusively for the UAE, as UN Comtrade data and Nigerian official data show. The figures reported by the Emirati authorities dwarf those reported by the authorities of the other importing countries and are also much higher than their mirror image, namely the figures on gold exports communicated to SWISSAID by the MMSD.

It is difficult to interpret the evolution of the UAE’s imports between 2010 and 2022, notably because reliable data on gold production in Nigeria is lacking. However, a pattern can be observed: whereas the rise of the UAE’s imports in the first half of the 2010s can arguably be attributed to an actual growth of Nigeria’s production of mined gold, their fall in the second half of that decade is almost certainly due to another factor, namely Niger’s increasing role as a transit country for ASM gold from Nigeria, which is explained below.

Beside the UAE, the only other destination country worth mentioning is Switzerland. Until recently, only small quantities of – presumably ASM – gold were imported from Nigeria into Switzerland. The volumes shot up in 2022 as a result of the new partnership between Segilola and Metalor, a Swiss refinery. In other words, Switzerland now receives most, if not all, of Nigeria’s output of industrial gold. SWISSAID was not able to find a conclusive explanation for the 1-ton gap between the figures communicated by the MMSD and those reported to UN Comtrade by the Swiss authorities for the year 2022, which can be seen in the graph above. It might be due to the inaccuracy of MMSD data, but this would need to be confirmed.

For the years 2018–2021, Nigeria appears in the list of countries of origin published by the London Bullion Market Association (LMBA) (LMBA Country of Origin Data 2018–2022) only in connection with shipments of 95 kg of LSM gold to Switzerland in 2021 (which can be explained by the start of production at Segolila in the fourth quarter of 2021) and shipments of negligible quantities of “recycled gold” to refineries in “Europe and Africa” (22 kg in 2018 and 35 kg in 2021). It can therefore be assumed that, for those years, not LBMA-certified refineries but actors of another type were responsible for most imports of gold from Nigeria9.

For the year 2022, Nigeria appears in LBMA data in connection with shipments of almost 3 tons of LSM gold to Switzerland, which are most likely due to the fact that Metalor, an LBMA-certified refinery based in that country, started sourcing significant quantities of gold from the Segolila mine. That same year, 104 kg and 22 kg of “unprocessed” gold (a new category introduced by the LMBA in 2022) reached LBMA refineries in “Europe and Africa” and Germany, respectively.

Illegal gold exports

Estimates of the volume and value of gold that was trafficked out of Nigeria in the last decade vary widely. In 2020, PAGMI calculated using mirror data from UN Comtrade that 97 tonnes of gold valued at over USD 3 bn has been smuggled between 2012 and 2018 ( FMINO 2020; see also Medium 2020). More recently, the head of MMSD, Uche Ogah, was quoted in the media claiming Nigeria had lost revenue estimated at USD 5 bn in the past six years (This Day Live 2022) or even USD 9 bn a year (Bloomberg 2021, The Cable 2021) due to gold smuggling. His predecessor Alhaji Bawa Bwari mentioned lower figures for the same phenomenon: about 18 tonnes of gold worth USD 900 mln lost between 2016 and 2018 (Punch 2019, cited in ENACT 2020: 2). Finally, NEITI was quoted in the media as having calculated that Nigeria had lost nearly USD 54 bn to illegal gold mining and smuggling between 2012 and 2018 (Business a.m. 2021). These are all impressive figures, which could be too high due to a confusion between the value of the gold that was smuggled out of Nigeria and the revenue that the Nigerian state could have derived from its production and trade had it been able to charge fees and levy taxes and duties.

It is widely acknowledged that the main destination of undeclared gold exports from Nigeria is the UAE. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) writes in its 2021 Annual economic report about a “substantial outflow of gold, from Nigeria to the UAE, without evidence of requisite royalty payments and approved certificate of exportation”. The report also contains a mention of the Federal government of Nigeria negotiating a bilateral agreement with its Emirati counterpart to “track [this] huge illegal movement of gold from Nigeria to Dubai” (CBN 2021: 85, see also Vanguard 2021).

Undeclared gold from Nigeria reached the UAE by various routes during the 2010s. One of them is a direct route: the high figures reported by the Emirati authorities to UN Comtrade as imports of gold from Nigeria during the first half of the decade indicate that this gold was most likely shipped directly to Dubai at that time. Uche Ogah’s statement that “gold smuggling in Nigeria is often done using private jets” (The Street Journal 2021) suggests that this traffic involved mainly transportation by air – and potentially individuals belonging to the country’s economic or political elites.

Other routes by which gold from Nigeria reaches the UAE are indirect and pass through neighbouring countries. Several accounts published in recent years mention them, in particular the route through Niger. For instance, a report on ASM of tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold (3TG) in Nigeria, which is based on field research and interviews with people on the ground, states that “the majority of gold [from Nigeria] is thought to be smuggled by road to the Republic of Niger, often through Niger State” (BGR 2022: 70, see also 10). Likewise, a report on illegal mining and rural banditry in North-West Nigeria states that “gold has become one of the most routinely smuggled commodities in Nigeria. Much of it is traded on the international market through neighbouring Niger and Togo to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates by a syndicated smuggling ring” (ENACT 2020b: 4, see also ENACT 2020a). Finally, one media article advances that “on a monthly basis, about 500 kg of gold is reportedly smuggled out of the country into neighbouring countries like Niger and Togo from where the raw materials find their way to the Middle East” (Nairametrics.com 2020).10

Tax differentials are an important driver of regional gold smuggling. As Nere Teriba, vice-chairman of the licensed Nigerian refinery Kian Smith Trade & Co., explained to the media: “If you have Benin Republic and Togo charging zero per cent royalty, Niger Republic one per cent and Nigeria three per cent, coupled with open borders as a result of ECOWAS treaty, it is regular economics; the gold will go to where it is zero per cent” (Punch 2022). The traffic is also sustained by corruption, in particular state capture: “Illegal miners often front for politically connected individuals who collaborate with foreign nationals and corporations to sell gold and routinely smuggle it to Dubai through neighbouring Niger and Togo” (ENACT 2020a).

It is likely that the direct route to the UAE was predominant in the first half of the decade and that the indirect one through Niger has progressively supplanted it in the second half. A comparison of gold imports into the UAE from Nigeria with those from Niger (see corresponding country profile) shows that there is a strong correlation between the two phenomena: imports from Nigeria drop in the same years where imports from Niger rise. This suggests that a shift from direct flows of Nigerian gold to the UAE to indirect ones may have occurred in those years. The same pattern can also be observed in the case of Benin (see corresponding country profile), which suggests that the shift may have involved other countries beyond Niger.11 However, the case of Togo (see corresponding country profile) seems to be different: in those years where imports of gold from Nigeria declared by the Emirati authorities drop, those from Togo drop as well. Perhaps the explanation in that case is Niger’s increasingly important role as a transit country for Nigerian gold destined for Dubai. All this lends credence to the idea that the UAE have continued to source vast quantities of undeclared gold from Nigeria even when their officially reported imports were at their lowest (i.e. in 2021). And in the absence of evidence to the contrary, one can assume that this traffic is still ongoing.

- MMSD’s response to SWISSAID, 9 October 2023. It should be noted that there are several publicly available sources for official figures on gold production in Nigeria. These include the MMSD’s annual reports, the Central Bank of Nigeria’s annual reports and annual economic reports, the National Bureau of Statistics’ mineral production statistics and state disaggregated mining and quarrying data. Solid minerals reports and annual reports by the Nigerian chapter of the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (NEITI) are another source, which relies mainly on official data. The figures released by these various entities do not always tally. SWISSAID has not enquired into this issue and has decided to rely exclusively on those originating from the MMSD.↩

- Nigerian customs statistics from 2022, obtained via a paid database; confirmed by Metalor to SWISSAID, 18 January 2023. See also SWISSAID 2023: 13.↩

- Comment of an expert of the Nigerian gold sector on SWISSAID’s analysis, 13 September 2024.↩

- Another source mentions an estimate of Nigeria’s ASGM production of 14 tonnes, but does not specify where this figure comes from or how it was calculated (PlanetGold 2021).↩

- There is a mistake on p. 61 of this report: the total should read 64 kg, not 39 kg.↩

- The only exceptions are gold exports to Nigeria of 165 kg in 2014 and 125 kg in 2016 reported by the British authorities and the Italian ones, respectively.↩

- The Nigerian authorities also reported data on gold exports to UN Comtrade, but there are not figures for the years prior to 2018 and the figures on weight reported thereafter are not consistent with those communicated to SWISSAID by the MMSD. For example, Nigeria exported 148 kg and 19,360 kg of gold in 2021 and 2022, respectively, according to UN Comtrade, whereas the MMSD communicated to SWISSAID gold exports of 373 kg and 4,704 kg for those years.↩

- UN Comtrade data for 2023 and 2024 was not complete or final at the time of writing. Therefore, SWISSAID’s analysis only covers ten years until 2022.↩

- Country of origin data released annually by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) is a key source of information on the destination of gold from individual countries, including African countries. It originates from the reports that all refiners certified according to the LBMA standard have to submit. However, the LBMA then only releases this data in aggregated form (per country, when four or more refineries are based in the same country, otherwise per region), to avoid disclosing information about each individual refinery. In the past, this data only appeared in the LBMA’s Sustainability and Responsible Sourcing Reports (see LBMA 2020: 37 for 2018, LBMA 2021: 47 for 2019, LBMA 2022: 28 for 2020 and LBMA 2023: 32 for 2021). Since 2024, it can be accessed on a dedicated webpage: LBMA Country of Origin Data.↩

- The article by Nairametrics does not specify the source of the information, but SWISSAID realised that 500 kg per month (6 tonnes per year) corresponds to the total weight for three years (18 tonnes) mentioned by former head of MMSD Alhaji Bawa Bwari while he was still in office (Punch 2019).↩

- SWISSAID has found indications that gold is smuggled from Nigeria to Benin but little hard evidence thereof. Yet, smuggling more generally takes place on a large scale between these two countries. Therefore, it is highly plausible that gold could be among the many commodities that cross their porous border on a regular basis.↩